Part 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

During the 1990s, a few years before my father, Dave, passed away in December of 2000, he wrote a 35-page autobiography. Excerpts from it will be published here, as companions to the diaries my mother, Dorothy, kept in 1945 and 1946—the year she met Dave. My dad was born in 1927, in Hamilton, Ohio. The family eventually moved to the south side of Chicago.

Part 4

Rags and Old Iron

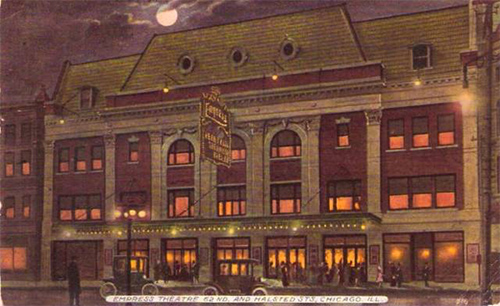

I wanted desperatately to go to the show–the movies–but I needed money for that. The Empress theater had the latest chapters of Don Winslow of the Navy, Flash Gordon, and Secret Agent X9. The problem, however, was finding a nickel to get in to see them. We usually solved it by scavenging in the alleys and streets for anything that we could sell.

The Empress movie theater, at 62nd & Halsted Streets

We'd offer a gunny sack full of old rags or a ball of foil from the insides of cigarette packages to the horse-and-wagon man. He would come down the alleys singing out “Rags, old iron,” which we heard at the time as “Rags olion.” He'd weigh our stuff in the back of the wagon on an old scale, always knowing when we had hidden rocks or bricks in the bag to increase its weight. I can still see him laying the balls of tinfoil on top of the wagon boards, and chopping through them with a cleaver, making sure the foil wasn't wrapped around a stone.

A rag man of the 1930s, talking to passersby

Frustrated one day at not collecting the five cents for a movie, I decided to take the lead ingot my mom used as a door prop, and sell it to the rag man. Of course, mom found out, and I can still feel the broom she hit me with.

My brother Charlie and I had the job of providing kindling wood for our cook stove. It burnt coal after starting the fire with scraps of wood and paper. We'd walk the alleys behind stores, gathering wooden crates which, at the time, were used to transport produce. We'd break up the crates, filling up our wagon with the scraps which we'd then store down in our dirt-floor basement.

We also bundled kindling wood which we'd then sell door-to-door for ten cents per bundle. We didn't share that money at home, but on the other hand, we provided through work, pilfering, and other hustles, for most of our meals and all our other needs. With five cents, I could buy a double popsicle or fudgesicle, with the added chance of having one of the sticks marked “Free,” which would entitle me to another one at no charge.

There was a store on our block that had a little, tinkling bell that alerted the store owner to come out from his back apartment and into the store area. In the store one afternoon with my brother, and before the owner came out, I spotted, behind the counter, a glass jar full of these “Free” sticks. We left the store with all of them, being mindful to never to redeem any of the sticks at that particular business.

One night, mom took me with her to see Sergeant York, starring Gary Cooper, at the Halsted theater. It was the only time she ever brought me to a movie, possibly because she may have been in love with the star. To this day, I can still sense her presence, sitting next to me in the dark.

Sergeant York, starring Gary Cooper

My first signs of rebellion–towards routine, authority and, especially, school–began in 1937 or '38, when I was about ten years old. I ditched classes as often as possible. But being absent from school for more than one day required bringing a note to the teacher upon returning. However, I wasn't smart enough. I'd stay out for two, three or more days consecutively. What I did or where I went during those days, I don't recall, except for one time. I remember standing in the warm doorway of the post office at 39th Street. Because I was always wearing tennis shoes, I suffered from cold, wet feet, despite that mom would cut cardboard into a sole pattern, and insert the forms into my shoes to plug the holes. She'd also tape over the loose, flapping toes. Charlie and I could have stolen, or even bought, new shoes. But shoes and clothes didn't hold much importance to us. Being outdoors, free, was what mattered.

During one of my class-cutting episodes, I was lurking in the alley behind our house for some reason. Of course, mom spotted me. It turned out that a truant officer had visited her that day, causing her to have my brother Charlie and the neighbors scour the neighborhood looking for me. I was cornered by Charlie on one side and mom on the other. Trussed-up with belts and a rope, I was led right back to the school. Once there, the principal questioned me. “Why did you ditch school?” I made up a story about some big school kids beating me up, making me afraid to attend classes. Everyone bought the story, but the incident cured me of any ideas of ever cutting school again.

* * *

End of Part 4

Part 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

|